Painting of South Sea Bubble speculators by Edward Matthew Ward, Tate Gallery. Wikimedia

Painting of South Sea Bubble speculators by Edward Matthew Ward, Tate Gallery. Wikimedia

Coronavirus has caused a great deal of stock market turbulence and, somewhat inevitably, comparisons have been made to the volatility caused by the South Sea Bubble 300 years ago. This was the moment when, in 1720, share prices in London boomed and then fell sharply. It is thought of as a major economic disaster and huge scandal.

In reality, it was a scandal but not much of a disaster. While some investors lost out from the speculation, it did not make much of a dent in the wider economy, unlike the more recent crashes of 1929 and 2008 – and what the long-term economic effects will be from COVID-19.

The episode shows how a perceived crisis can be the subject of intense public outcry and moral panic, even when people do not understand what has happened. It shows how the narrative told to the public can easily diverge from the truth: fake news, if you will.

What actually happened

The real reasons behind the bubble are complex. The South Sea Company, which gave its name to the event, helped the government manage its debt and also traded enslaved Africans to the Spanish colonies of the Americas. The government struggled to pay holders of its debt on time and investors had difficulty selling on their debt to others due to legal difficulties.

So debt holders were encouraged to hand their debt instruments to the South Sea Company in exchange for shares. The company would collect an annual interest payment from the government, instead of the government paying out interest to a large number of debt-holders. The company would then pass on the interest payment in the form of dividends, along with profits from its trading arm. Shareholders could easily sell on their shares or simply collect dividends.

The debt management and slaving aspects of the company’s history have often been misunderstood or downplayed. Older accounts state that the company did not actually trade at all. It did. The South Sea Company shipped thousands of people across the Atlantic as slaves, working with an established slave trading company called the Royal African Company. It also received convoy protection from the Royal Navy. Shareholders were interested in the South Sea Company because it was strongly backed by the British state.

By the summer of 1720, South Sea Company shares became overvalued and other companies also saw their share prices increase. This was partly because new investors came into the market and got carried away. In addition, money came in from France. The French economy had undergone a huge set of reforms under the control of a Scottish economist called John Law.

Law’s ideas were ahead of his time, but he moved too quickly. His attempts to modernise France’s economy did not work, partly because the rigid social system remained unchanged. The French stock market boomed and then crashed. Investors took their money out of the Paris market – some moved it to London, helping push up share prices there.

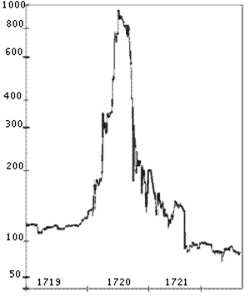

The rapid rise and fall of South Sea Company shares. Wikimedia

The rapid rise and fall of South Sea Company shares. Wikimedia

Once the South Sea Bubble had started to inflate, it attracted more naive investors and those who would prey upon them. While it was clear that the high prices were unsustainable, canny speculators bought in hoping to sell out in time. This pushed up prices even more, in the short term. The stock price went up from £100 in 1719 to more than £1,000 by August 1720. The inevitable crash back down to £100 per share by the end of the year came as a shock to those who thought they could make their fortunes overnight.

The backlash

The crash provoked huge public outcry. Politicians demanded an inquiry. South Sea Company directors were accused of treason and fraud. Poems, plays and satirical prints criticised the market and those in it. The chancellor of the exchequer was briefly locked up in the Tower of London. The company’s directors were forced to appear in front of parliament.

The amount of noise generated by these reactions helped make the South Sea Bubble famous. From then on in, it became a byword for financial scandal. Yet many people could not really explain what had happened. Perhaps surprisingly, economic historians can find little evidence of a prolonged economic recession. The bubble burst but without the major effects of later financial crises.

William Hogarth’s caricature of the bubble. Wikimedia

William Hogarth’s caricature of the bubble. Wikimedia

So why all the fuss? First, the crash happened in the early days of the stock market. There was no body of financial theory or financial journalism which could help explain it to laypeople. They turned instead to conspiracy theories or strange ideas about people becoming gambling mad.

Second, there was talk of people being given their money back. This gave losers every incentive to talk up their losses. It is human nature to complain, even about a small loss. The popular perception is that great fortunes were destroyed, but there is little evidence of this beyond one or two cases.

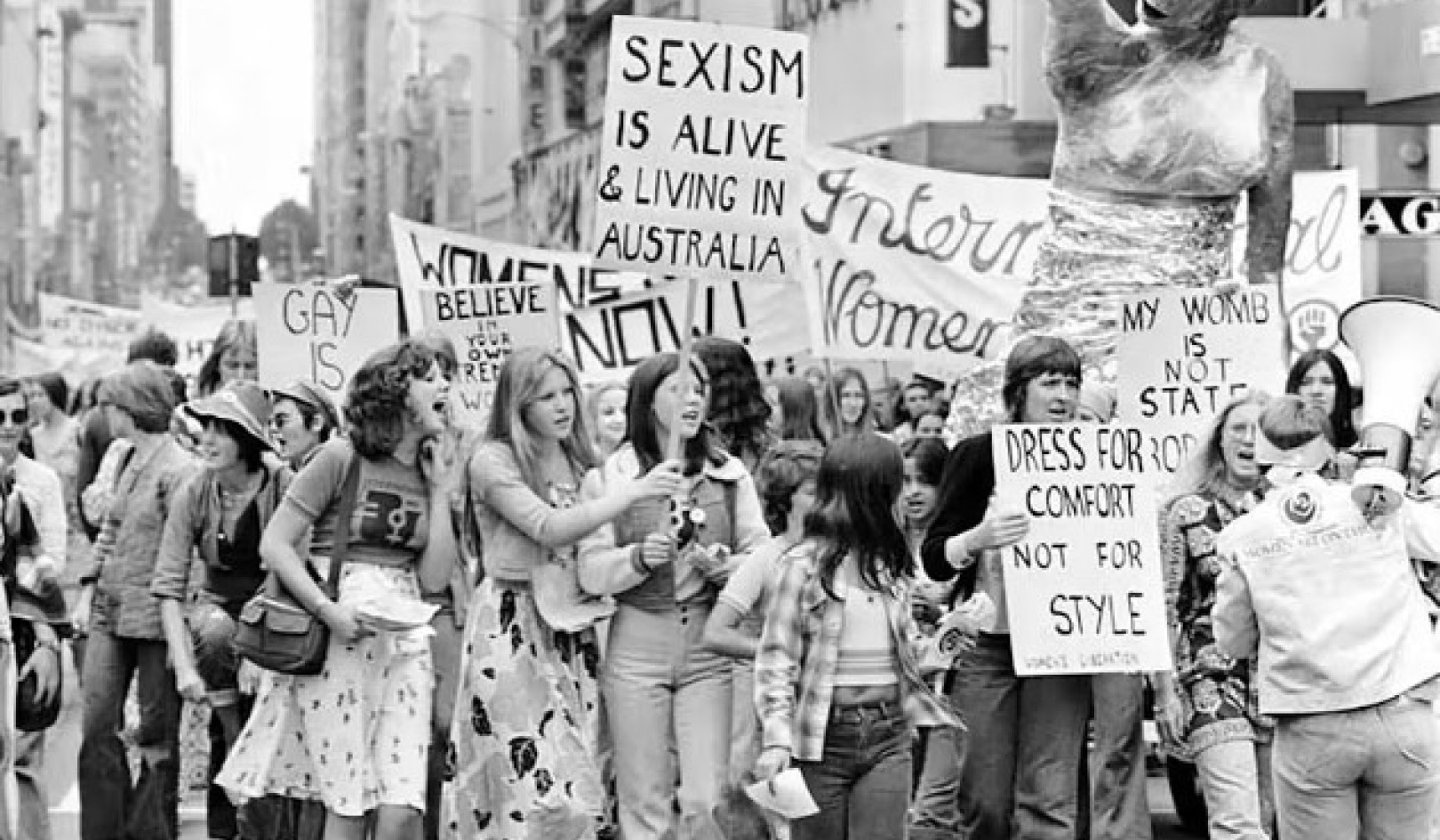

Third, this was a glorious opportunity for schadenfreude and various sorts of prejudice to be expressed. Female investors were lampooned by misogynists. Foreigners and various religious groups were the subject of racist commentary. There was no expert analysis available and commentators, with no real understanding of finance, provided scandal and scapegoating instead of accurate reporting.

The South Sea Bubble has been a symbol of financial crisis for 300 years. But like other more modern crises, its public image diverges from the reality. The same probably can’t be said for the COVID-19 pandemic, which will have a much more deep and lasting effect on the world economy.![]()

About The Author

Helen Paul, Lecturer in Economics and Economic History, University of Southampton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recommended books:

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by Thomas Piketty. (Translated by Arthur Goldhammer)

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty analyzes a unique collection of data from twenty countries, ranging as far back as the eighteenth century, to uncover key economic and social patterns. But economic trends are not acts of God. Political action has curbed dangerous inequalities in the past, says Thomas Piketty, and may do so again. A work of extraordinary ambition, originality, and rigor, Capital in the Twenty-First Century reorients our understanding of economic history and confronts us with sobering lessons for today. His findings will transform debate and set the agenda for the next generation of thought about wealth and inequality.

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty analyzes a unique collection of data from twenty countries, ranging as far back as the eighteenth century, to uncover key economic and social patterns. But economic trends are not acts of God. Political action has curbed dangerous inequalities in the past, says Thomas Piketty, and may do so again. A work of extraordinary ambition, originality, and rigor, Capital in the Twenty-First Century reorients our understanding of economic history and confronts us with sobering lessons for today. His findings will transform debate and set the agenda for the next generation of thought about wealth and inequality.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.

Nature's Fortune: How Business and Society Thrive by Investing in Nature

by Mark R. Tercek and Jonathan S. Adams.

What is nature worth? The answer to this question—which traditionally has been framed in environmental terms—is revolutionizing the way we do business. In Nature’s Fortune, Mark Tercek, CEO of The Nature Conservancy and former investment banker, and science writer Jonathan Adams argue that nature is not only the foundation of human well-being, but also the smartest commercial investment any business or government can make. The forests, floodplains, and oyster reefs often seen simply as raw materials or as obstacles to be cleared in the name of progress are, in fact as important to our future prosperity as technology or law or business innovation. Nature’s Fortune offers an essential guide to the world’s economic—and environmental—well-being.

What is nature worth? The answer to this question—which traditionally has been framed in environmental terms—is revolutionizing the way we do business. In Nature’s Fortune, Mark Tercek, CEO of The Nature Conservancy and former investment banker, and science writer Jonathan Adams argue that nature is not only the foundation of human well-being, but also the smartest commercial investment any business or government can make. The forests, floodplains, and oyster reefs often seen simply as raw materials or as obstacles to be cleared in the name of progress are, in fact as important to our future prosperity as technology or law or business innovation. Nature’s Fortune offers an essential guide to the world’s economic—and environmental—well-being.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.

Beyond Outrage: What has gone wrong with our economy and our democracy, and how to fix it -- by Robert B. Reich

In this timely book, Robert B. Reich argues that nothing good happens in Washington unless citizens are energized and organized to make sure Washington acts in the public good. The first step is to see the big picture. Beyond Outrage connects the dots, showing why the increasing share of income and wealth going to the top has hobbled jobs and growth for everyone else, undermining our democracy; caused Americans to become increasingly cynical about public life; and turned many Americans against one another. He also explains why the proposals of the “regressive right” are dead wrong and provides a clear roadmap of what must be done instead. Here’s a plan for action for everyone who cares about the future of America.

In this timely book, Robert B. Reich argues that nothing good happens in Washington unless citizens are energized and organized to make sure Washington acts in the public good. The first step is to see the big picture. Beyond Outrage connects the dots, showing why the increasing share of income and wealth going to the top has hobbled jobs and growth for everyone else, undermining our democracy; caused Americans to become increasingly cynical about public life; and turned many Americans against one another. He also explains why the proposals of the “regressive right” are dead wrong and provides a clear roadmap of what must be done instead. Here’s a plan for action for everyone who cares about the future of America.

Click here for more info or to order this book on Amazon.

This Changes Everything: Occupy Wall Street and the 99% Movement

by Sarah van Gelder and staff of YES! Magazine.

This Changes Everything shows how the Occupy movement is shifting the way people view themselves and the world, the kind of society they believe is possible, and their own involvement in creating a society that works for the 99% rather than just the 1%. Attempts to pigeonhole this decentralized, fast-evolving movement have led to confusion and misperception. In this volume, the editors of YES! Magazine bring together voices from inside and outside the protests to convey the issues, possibilities, and personalities associated with the Occupy Wall Street movement. This book features contributions from Naomi Klein, David Korten, Rebecca Solnit, Ralph Nader, and others, as well as Occupy activists who were there from the beginning.

This Changes Everything shows how the Occupy movement is shifting the way people view themselves and the world, the kind of society they believe is possible, and their own involvement in creating a society that works for the 99% rather than just the 1%. Attempts to pigeonhole this decentralized, fast-evolving movement have led to confusion and misperception. In this volume, the editors of YES! Magazine bring together voices from inside and outside the protests to convey the issues, possibilities, and personalities associated with the Occupy Wall Street movement. This book features contributions from Naomi Klein, David Korten, Rebecca Solnit, Ralph Nader, and others, as well as Occupy activists who were there from the beginning.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.